Adding Mumble Support to Valheim

I'm taking a detour from my usual Rust side projects to dabble in something

new: Unity modding! I, like many others, have found myself addicted

obsessed highly invested in Valheim, a multiplayer viking

survival game that recently entered Steam Early Access. Lacking any built-in

voice capabilities, players use other platforms to communicate. Mumble, an

open-source voice chat program, has a cool feature where it can use in-game

position data to make it sound like your friends' voices actually come from

their characters. The trick is getting that data into Mumble.

Foundations

Because nothing exists in a vaccuum and everything we build is on the shoulders of giants, I'll first go over the basic modding setup and tools for exploration. Valheim is built with Unity and doesn't go though the IL2CPP converter, so pretty much all of its code ends up as a C# assembly. This makes it fairly easy to open up with a tool like ILSpy to decompile it and view the source. That helps understand how the game works, but what about actually adding code to it?

That's where BepInEx comes in. BepInEx is a modding framework and loader for Unity games that use C# for scripting. Installation is extremely simple - basically just dropping its files into the game installation directory. The only issue with this is that Valheim ships with stripped Unity assemblies. They've had unneeded functionality removed, so they only contain what the game actually uses. BepInEx, unfortunately, requries some of that removed functionality, and it crashes immediately when installed. Luckily, some kind soul has put together a package that includes the un-stripped Unity assemblies.

Lastly, there are a couple of utility mods that make the the process building

a new one a lot simpler. UnityExplorer provides a handy

interface for browsing and poking at Unity GameObjects (and some other

stuff) at runtime. ScriptEngine lets you reload plugins

without having to restart the game ever time you recompile it.

Mumble Link

Before diving into more Unity stuff, we need to understand what Mumble needs

to do its thing. If you're only here for the Unity stuff, this can be safely

skipped. Documentation is a bit sparse, but Mumble Wiki pages on Positional

Audio and Link have most of what's needed to get it

all connected. To boil down the "linking" process to its basics: the game and

mumble use a shared memory-mapped file with a layout that's understood by

both. The game updates this shared memory with location data every frame, and

mumble reads it fifty times per second. The shared memory has fields for

character and camera locations and headings, the game name, a player

identifier, a "context", and a "tick" counter, so we'll need a way to get all

of these values from the game. Most fields seem fairly self-explanatory, but

context warrants a bit more. If two players have the same context, they'll

get directional audio from each other. If they have different contexts,

They'll just get normal non-directional audio. This will be important later.

Platform Differences

Linking a game to Mumble doesn't require any Mumble-specific libraries - it's all done via standard OS functionality. Unfortunately, this means that the exact mechanism differes slightly between Unix-like systems and Windows.

The Mumble Link example code for Windows uses the File Mapping C API:

HANDLE hMapObject = ;

lm = ;

The Unix-like example code uses the POSIX shared memory API:

char memname;

;

int shmfd = ;

lm = ;

The end result is the same: lm points to a region of memory that's the size

of LinkedMem and can be shared by the game and Mumble processes.

The example code is in C, but our plugin is going to need to be in C#, so some porting is going to be required. C#, being extremely Windows-y, makes the Windows case quite straightforward:

memoryMappedFile = MemoryMappedFile.;

byte* tmp = null;

memoryMappedFile

.

.SafeMemoryMappedViewHandle

.;

ptr = tmp;

For the POSIX case, it's a bit less straightforward. There aren't any

built-in ways to call the necessary functions that I could find, so the

easiest approach seemed to be to call libc directly. Fortunately, C# makes

this quite easy:

// In a class definition somewhere.

private static extern int shm_open([MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPStr)] string name, int oflag, uint mode);

private static extern uint getuid();

private static extern void* mmap(void* addr, long length, int prot, int flags, int fd, long off);

// In the constructor

fd = ;

ptr = ;

DllImport allows you to declare external functions along with the shared

library they're defined in. All loading of the shared library happens at

runtime, so it pretty much "just works," with the added benefit of not

throwing linking errors on Windows as long as you don't try to call the

methods. One thing I found really cool is the MarshalAs tag on the first

argument to shm_open. This is an attribute that can be placed on extern

function arguments that tells the runtime how to convert the type in the

declaration to what the function actually expects. In this case, it takes our

string and turns it into a null-terminated char* in the usual POSIX

fashion.

Memory Layout

When the Mumble Link memory layout was defined, a very unfortunate decision was made. The C version is defined like so:

;

We're just going to ignore the odd DWORD there. The Microsoft Data Types

Specification defines it as a 32-bit integer, so it's exactly

the same size as the UINT32's that are used elsewhere. The real egregious

type choice is wchar_t. Special care was taken to ensure that every other

type had the same width regardless of platform/compiler, except the fields

that are strings. The CPP reference states that wchar_t is

"Required to be large enough to represent any supported character code point."

On most systems, this means that it's an unsigned 32-bit integer and can

simply contain the un-encoded unicode codepoint. On Windows, however, they're

half that size - 16 bits, and contain UTF-16-encoded characters. This means

that the LinkMemory has a different layout on different systems, and some

extra special care has to be taken in modern languages that assumes that

types are consistent across platforms. On Linux, this means that the string

fields are fixed uint field[len], while on Windows, they're fixed ushort field[len]. The encoding used to write them also needs to be UTF32 and

Unicode respectively.

I'm not sure why the strings were laid out this way. My best guess is that

it's from the days when pretty much everything in Windows was UTF-16, and

using wchar_t and wcsncpy kept the C interface consistent. It might have

made made sense when everything was written in C, but it only serves to make

my life more difficult today.

Putting It Together

Actually switching between the two implementations is pretty boring after the

memory layout was all figured out. There are two options: C-style #if

preprocessor directives that are evaluated at compile-time, or including both

versions in the assembly and switching between them at runtime. To avoid

having to compile and distribute both versions, I opted for the later. The

end result is a couple of interfaces with implementations for both Windows

and Linux:

public

public

Back to Unity

Now that the Mumble stuff is out of the way, all there is to do is to find

the data that we need, add it to the LinkFile, and increment its tick

counter. Easy, right?

Objects of Interest

For best results, we need both the character location and camera location.

Players expect to hear things in relation to the camera, regardless of how

the character is oriented, and expect to hear things coming from other

players' character rather than their orbiting camera. Thus, both positions

and headings are needed. We don't need the *Top vectors. Those are only

needed if you can tilt your head side to side in-game, like in first-person

shooters where you can lean around corners and such.

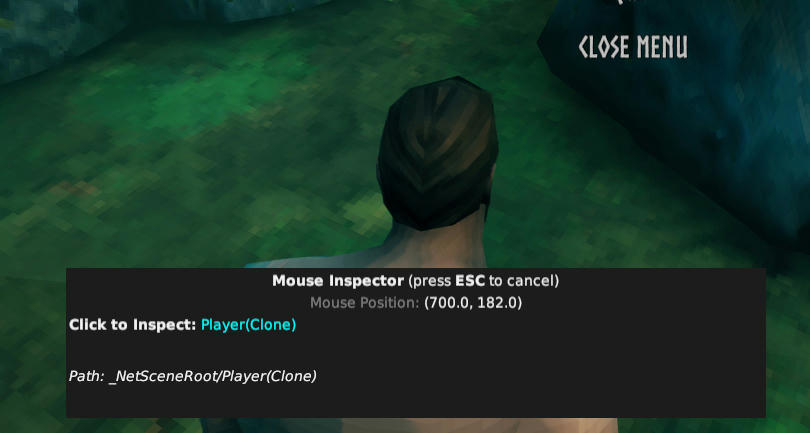

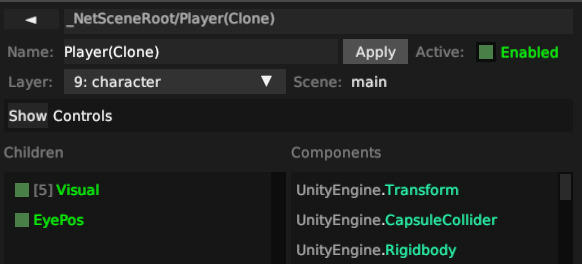

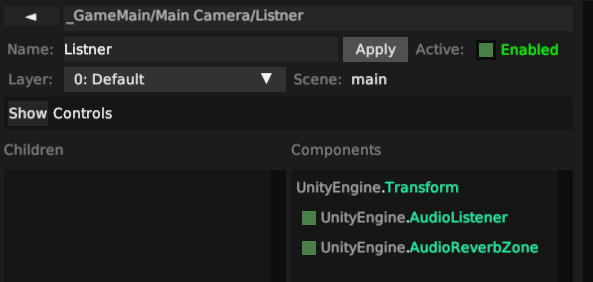

I did most of my investigation in UnityExplorer. After loading a character

into a world, there's a big obvious _GameMain object at the root of the

main scene. Seems promising, right? Inside _GameMain is a Main Camera,

score! The Main Camera object has a child named Listner. Its components

are extremely telling of their purpose.

Any game that has directional audio, regardless of voice chat, has to already

have some object with the exact position and heading information needed to

figure out where sounds are coming from. For Valheim, Listner is that

object, so it only makes sense to reuse it for our purposes. You can even

inspect its Transform (Unity speak for location info), check "Auto Update,"

and watch as the forward and position vectors change as you move the camera

around. Pretty neat!

The character information was a little trickier to find. I poked around in

_GameMain quite a bit without much luck, and explored some of the other

objects as well. _NetSceneRoot has gobs of children, most or all of which

seem to correspond to physical objects in the game world. Unfortunately,

there are over 200 pages of them to scroll through, so just stumbling across

the player object probably won't work. Luckily, UnityExplorer has a "Mouse

Inspector" mode. At the right angle, you can inspect the player object

Metadata

With the Listner and Player objects, we've got all of the location

information needed to feed to Mumble. So what about the things like the

context? On one hand, we could just set it to a static value and everyone

playing should get directional audio from each other. But what if some people

are connected to a different server? Putting aside how generally confusing

that would be, it would be even more confusing if you were hearing the

"ghost" of someone else directionally who wasn't even in your world. So

having separate contexts per world seems the way to go.

This ended up being more difficult to find than the player and camera

information. Eventually, after decompiling and grep'ing around the source, I

landed upon the ZNet class. This seems to be the connection manager for the

game, and is running even in singleplayer mode or as the host of a game. It

has a method to GetWorldName, which sounds perfect for use as a context

string.

As an added bonus, using the world name as the context allowed me to test the mod with steam in offline mode, so I didn't have to recruit a friend to babble at. By loading into the same world on different single-player sessions, both used the same context, so I could at least verify that I was in fact getting positional sound, even if I couldn't actually see the source of it. It does have the downside of this being a possibility in the event that two Mumble users are connected to two different servers with the same world name, but that seems like an acceptable edge case to me.

The Mod Itself

The basic project structure is pretty well covered by the BepInEx

Tutorial, so I won't rehash it here. The "meat" of it is

how and when it decides to link to Mumble. C# scripts in Unity implement the

MonoBehavior interface. They have a number of methods that are called at

various points in their lifetime. The ones we care about are Awake and

FixedUpdate.

Awake runs just after the object is instantiated. In the case of BepInEx

plugins, this is close to when the game starts. I use it to figure out the

platform that it's running on, and select the proper Mumble Link

implementation.

void

FixedUpdate runs on a fixed interval (shocker, right?) and is intended to

be used for things like physics calculations that aren't framerate-dependent.

This makes it the perfect choice to gather our location data and send it off

to Mumble.

unsafe void

Locating the GameObjects is an inefficient process, so we only want to do

it once, and then keep them around until they're no longer valid.

findGameObjects handles all of this for us:

private bool

private static bool

Init is pretty boring but I'll include it just for completeness' sake.

unsafe void

Bonus for the Modern Viking

Some may enjoy playing with Mumble's positional audio set up such that they

can't hear people who are too far away. But what about when they need to talk

to someone halfway across the world? A feature like

Phasmophobia's walkie-talkie would be neat. In Phasmophobia,

voice chat is mandatory, and is all positional by default. You have a button

you can press, however, to speak to everyone in the game, regardless of where

you are in relation to each other. This is easy enough to simulate with some

clever manipulation of the context field.

Recall that two players with the same context will hear each other positionally, but if they have different contexts, they'll get "normal" audio from each other. We can therefore keep track of the original context, and set it to gibberish while a key is held down, thus making your context different from everyone else's and temporarily disabling positional audio. It also lets you listen in on everyone else independent of positions.

The easiest way to accomplish this is with the KeyboardShortcut

configuration option for BepInEx. By adding this to the Awake method, a

configuration file gets generated, and mods like

BepInEx.ConfigurationManager can edit the setting.

globalVoice = Config.;

It can then be checked in the Update method like so:

void

private void

private void

There's likely a better way to accomplish the viking walkie-talkie effect via server-side scripts and clever use of groups and ACLs, but this approach is minimally invasive and doesn't require any additional configuration.

Source

Full source for the plugin can be found here, and the compiled version can be downloaded from the Releases. Bug reports are always welcome, as are suggestions for improvement!